https://www.archives.gov/citizen-archivist/

Reviewed by Hannah Pryor, University of Louisville Archives & Special Collections [PDF Full Text]

Introduced in 2010 by past Archivist of the United States David Ferriero, Citizen Archivist is a web-based, crowdsourced transcription and metadata program hosted by the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).[1] The online dashboard launched in 2011 and provides a home page for eponymous volunteer “citizen archivists” to begin transcribing and adding tags to the digitized records in NARA’s catalog.[2] To get started, all users need to do is sign up for a free National Archives Catalog account that can be used across any federal website with the login.gov sign in service.

Figure 1. The Citizen Archivist homepage.

Due to the volume of records held by NARA, initiatives like Citizen Archivist help make digitized records accessible in a way that may not be possible otherwise. While digitization efforts are ongoing, citizen archivists can transcribe or tag any portion of records available and viewable in their catalog. NARA regularly promotes several different challenge levels of new Citizen Archivist “missions,” ranging from general record groups of interest, such as John F. Kennedy Assassination records and National Park reports, to more specialized volunteer skillsets, like transcribing eighteenth-century handwriting, formatting complex tables in Navy logbooks, and tagging the names of immigrants documented in Chinese Exclusion Act case files to make them accessible for genealogists. The dashboard (Figure 1) has a page for training resources that show users how to format transcriptions, create accurate tags, and handle the various types of records they might encounter. Volunteers are encouraged to contribute at their level of comfort, from basic tags to more complex transcriptions that may require subject-matter expertise.

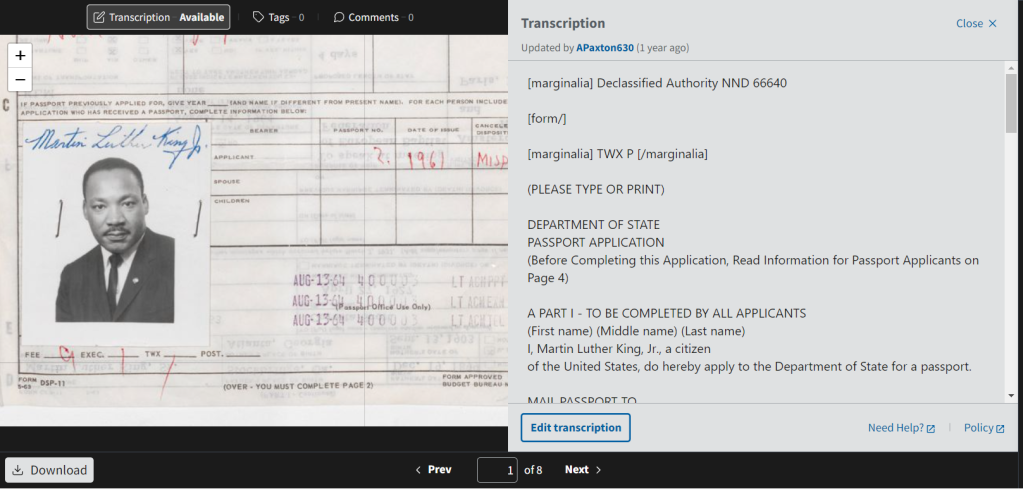

Figure 2. Transcription of a passport application signed by Martin Luther King Jr. (NAID 122674140). Courtesy of citizen archivist APaxton630.

Citizen Archivist uses a Wikipedia-style model for contributions, meaning volunteers can transcribe, tag, comment, and edit freely. This also includes reviewing and editing the work of other volunteers. The text transcription interface (Figure 2) is straightforward and user-friendly, although, like any web-based editor, it is possible to lose your work if your internet connection is not stable. The platform has a useful autosave feature that helps alleviate some of that potential frustration.

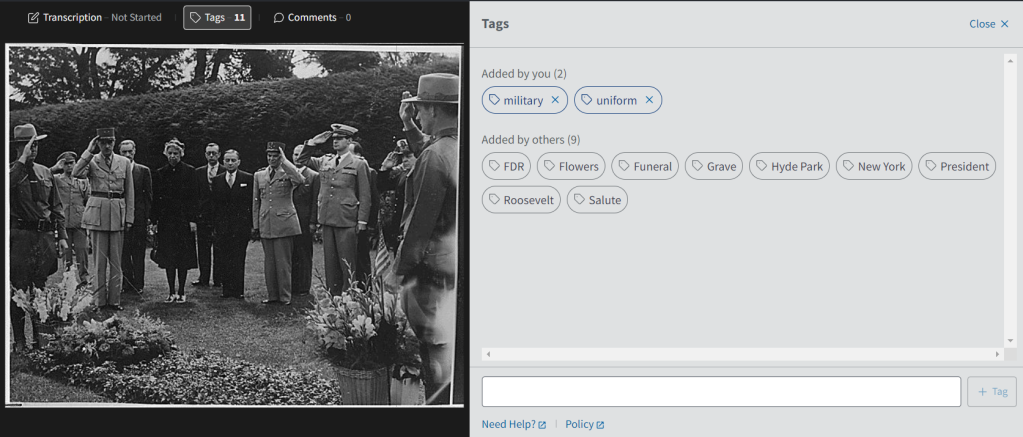

Figure 3. Crowdsourced tags for a photo of Eleanor Roosevelt at Franklin D. Roosevelt’s grave (NAID 197068). The name of the user who created a tag appears if you hover your mouse over it.

As with any crowdsourced initiative, the downside is that the extent to which something is described, and its quality, varies widely. More popular records may become over-described at a superficial level, while other records may have sporadic, inconsistent description. In my experience, some of the tags generated by users are not helpful access points to the materials, but that is to be expected of a quantity over quality approach. I believe the pros outweigh the potential cons—any level of description is still better than no description, and NARA may undertake reprocessing and redescribing projects for some record groups in the future.

The limited barriers to getting started is one of the program’s strengths—the only resource needed is a computer with internet access. This makes it a useful tool for engaging students with primary sources, history, and archival work. Because citizen archivists can contribute to any digitized public record, the record group of focus can be tailored to any kind of instructional or volunteer setting. For example, a class session about World War II could focus on records from Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidential terms, whereas a class on social justice could transcribe the inmate case files from the Bureau of Prisons. The Citizen Archivist resources page also provides activity instructions for an in-person group tagging competition. This use of gamification and the tailoring of topics of interest would be an effective approach to engaging many users.

As an archivist, I am a proponent of crowd-sourced metadata and transcription, especially if it helps non-professionals engage with aspects of their national history. I utilized the resource’s “Citizen Archivist Missions” to remain a part of the archival community during the COVID-19 pandemic because it was more difficult to make in-person professional connections. The label “citizen archivist” itself evokes a feeling of empowerment, letting anyone join in the efforts to make national records accessible to the public. There is a sense of discovery when viewing a new set of records and reading about a topic you might not have otherwise encountered. Overall, I would recommend Citizen Archivist to archivists who are searching for a free instructional tool or would like to get hands-on experience with national records.

[1] David Ferriero, “Cultivating Citizen Archivists,” National Archives and Records Administration AOTUS Blog, April 12, 2010, https://aotus.blogs.archives.gov/2010/04/12/cultivating-citizen-archivists/.

[2] Matthew Schaefer, “‘Tis the Season to Participate Online!” NARAtions, December 23, 2011, https://narations.blogs.archives.gov/2011/12/23/tis-the-season-to-participate-online/.